These projects are set in the context of the “Design in Science” initiative at the University of Cambridge (UK), which helped investigate collaboration between designers and scientists in the early stages of scientific research. They entail collaborative efforts between teams of designers and scientists engaged in research spanning diverse fields such as medicine, biochemistry, engineering, material sciences, chemical engineering, plant sciences, genetics, and chemistry.

P1-Fluid Handling System (Immunoassay)

2017 / Product/Graphic

Project Partners: Department of Biochemistry and Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge.

My role:

Project conception, co-researcher and co-designer (Including research, visualisation, ideation, prototyping and testing)

Design Goals

A biochemist team has developed a fluid-handling device using microcapillary film (MCF) for immunoassays, but it needs more ease of handling, multitesting capability, and compatibility with standard components. They seek an improved version to develop a safer, faster immunoassay procedure, compare it with existing techniques, and prepare for commercialisation. The project aimed to design an immunoassay device with enhanced handling, multitest capability and compatibility, ensuring safety, reliability, and cost-effectiveness. Deliverables include a prototyped device and a design specification document.

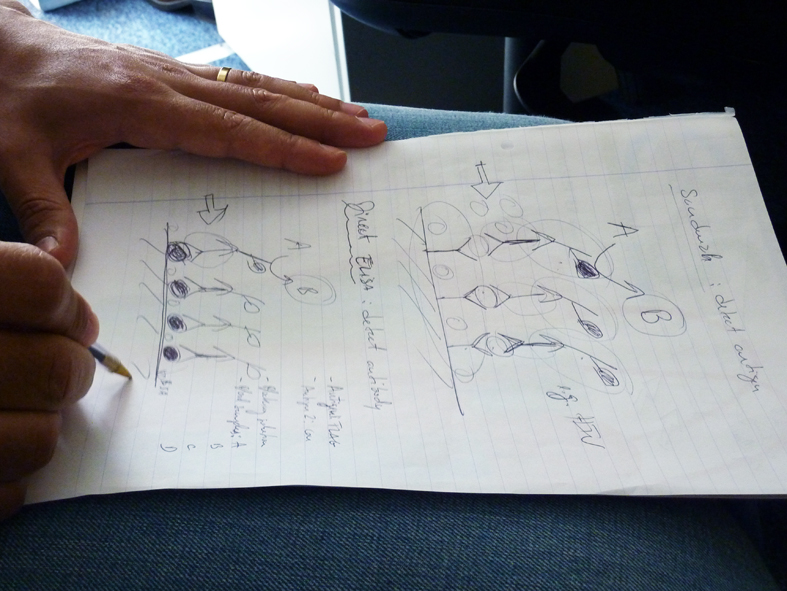

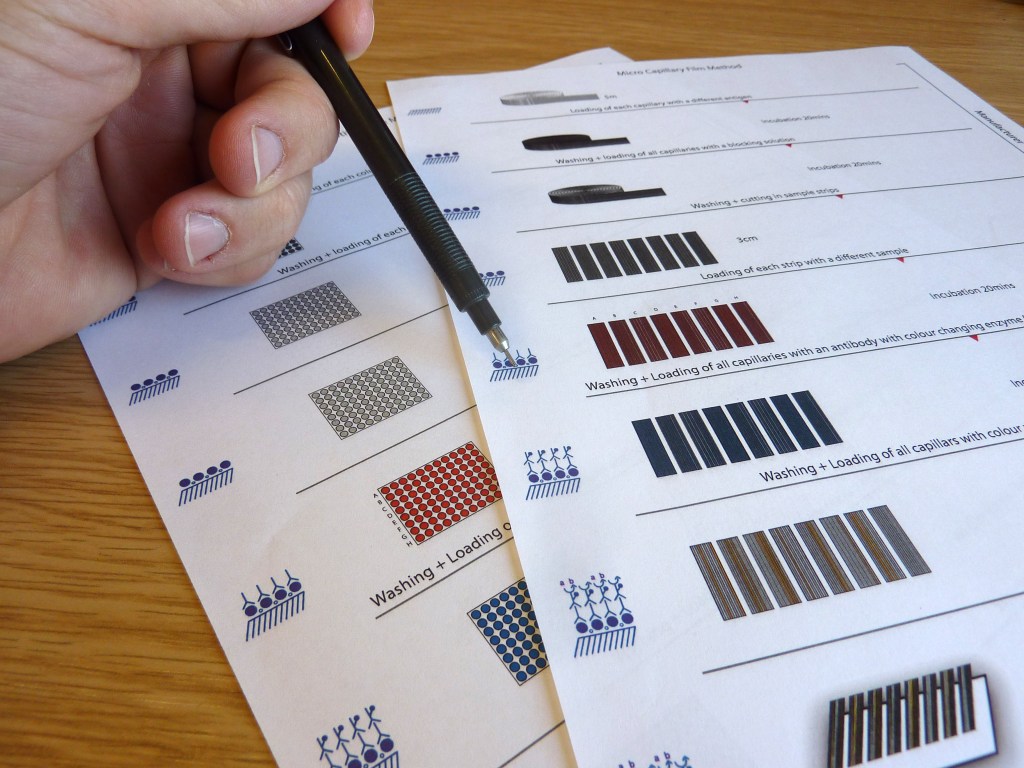

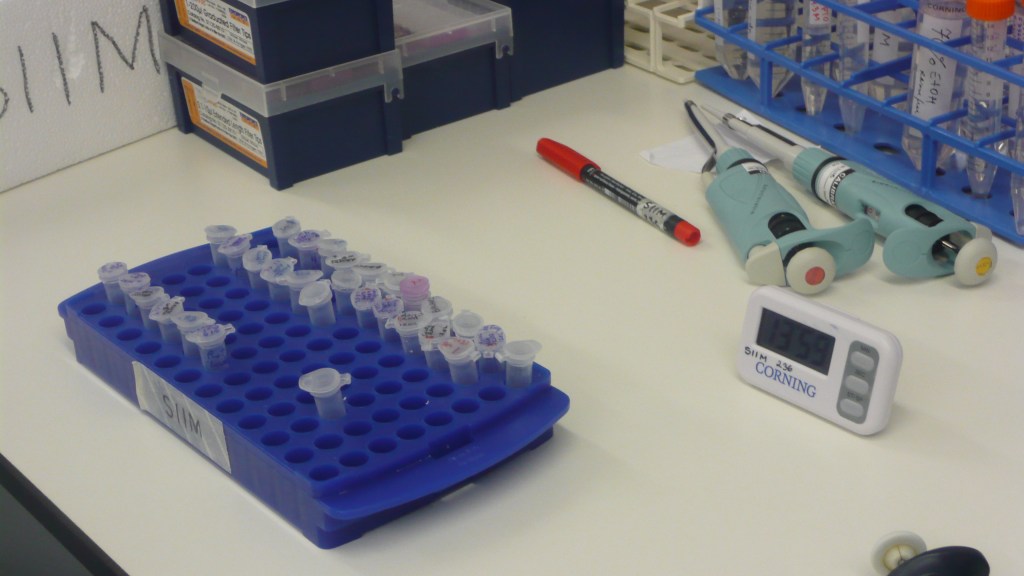

Initially, designers were introduced to the fluid handling device and the principles of immunoassays, a complex process with scientific underpinnings. Given its intricacies and non-observable aspects, designers conducted an observation day to grasp the practicalities and associate theoretical knowledge with real-world applications. This observation day provided invaluable insight, enabling designers to comprehend each step and the scientific principles involved. Scientists utilised a diagram with scientific symbols to explain non-observable aspects of the process, aiding designers’ understanding.

The design team devised diagrams illustrating each stage of the immunoassay process, associating them with corresponding scientific symbols. These diagrams were presented to the scientists, validating the designers’ comprehension of the process and its scientific concepts. Despite the design team’s initial unfamiliarity with immunoassay-related scientific concepts and terminology, the combination of observation, scientific explanation, and visual representation through diagrams facilitated effective communication between scientists and designers.

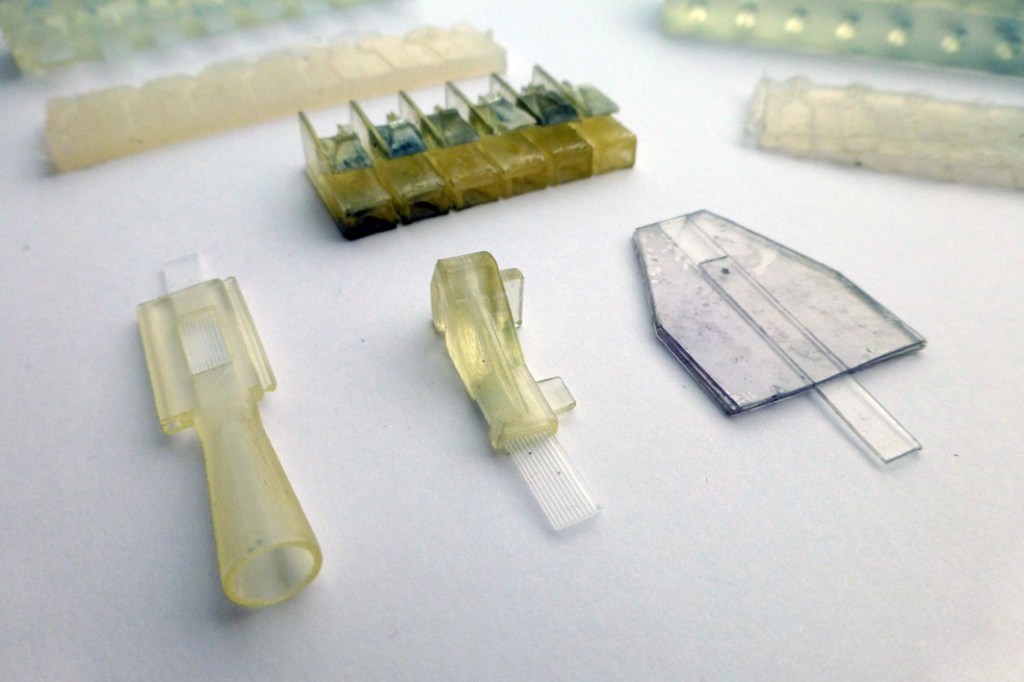

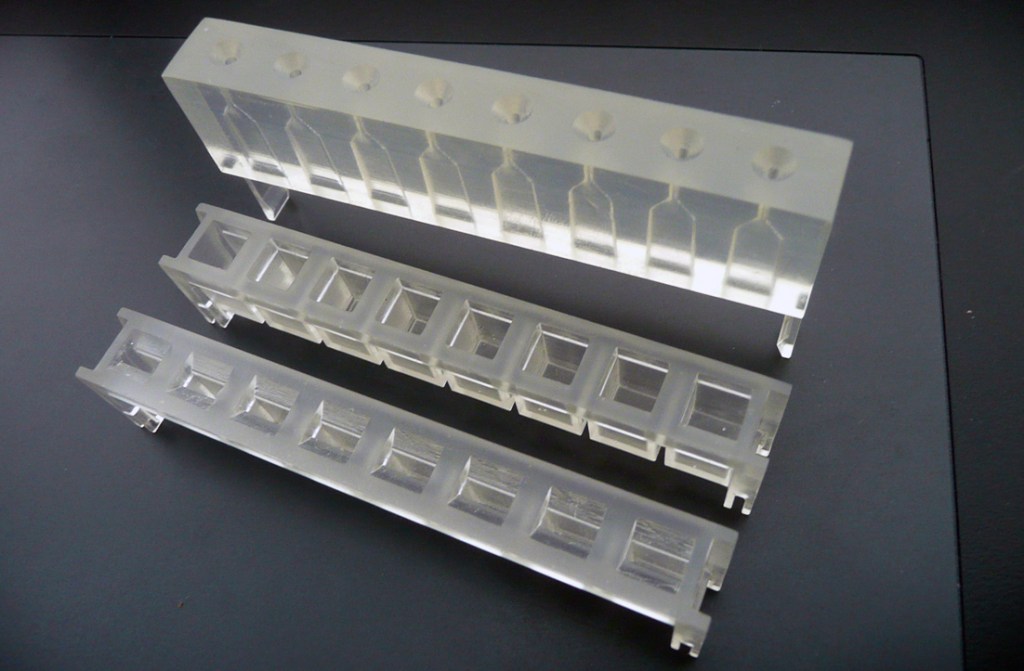

The design team initially borrowed standard equipment for immunoassays to test initial design concepts alongside sketch models. However, they realised that their designs needed to match the efficiency of the scientists’ models in liquid handling. Due to the small scale of their components, traditional sketch modelling techniques could have been more practical, leading them to use rapid prototyping, albeit a more expensive option. Consequently, consultation with scientists became more thorough. Interestingly, prototype presentations in scientific labs evolved into collaborative “design sessions,” where scientists and designers deliberated on various ideas and made crucial design decisions. Additionally, designers developed competing ideas, fostering group scrutiny and enhancing the design process.

Following several prototype iterations and collaborative ideation sessions between designers and scientists, a final prototype of the fluid handling system was developed and tested, meeting all design requirements. Additionally, the design team drafted a comprehensive design specification for the device’s future refinement. Leveraging the prototype and the design specification, the scientific team secured additional funding to manufacture 100 units for initial clinical trials.

P2-The Moss Table (Biophotovoltaics)

2017 / Digital/Visual/Conceptual/Participatory

Project Partners: Department of Plant Sciences and Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge.

My role:

Project conception, co-researcher and co-designer (Including research, visualisation, CAD work, ideation, prototyping and testing)

Design Goals

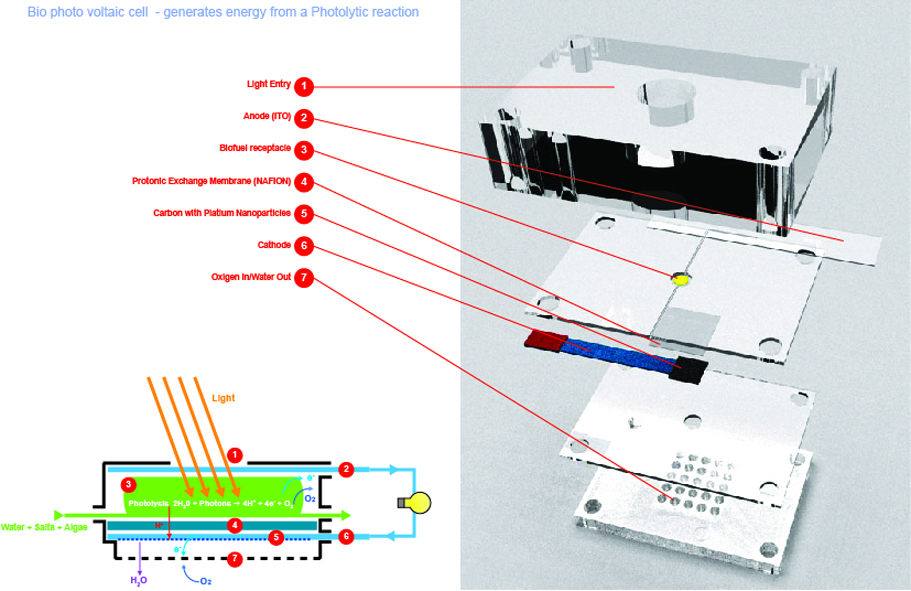

A team of scientists collaborated on developing Biophotovoltaic (BPV) technology, aiming to harness electric energy from photosynthetic processes. Using algae photosynthesis, their initial prototype laid the groundwork for theoretical development and data collection. They planned to showcase BPV technology at a science exhibition in London, aiming to educate the public about its potential impact. The project initially aimed to create an illustrative poster of the device to facilitate the public’s explanation of the technology during the event. Progressively, through the collaboration between designers and scientists, the project aim evolved and resulted in the creation of the moss table, a physical object intended to demonstrate the potential of Biophotovoltaic (BPV) technology and how it might be applied in the future.

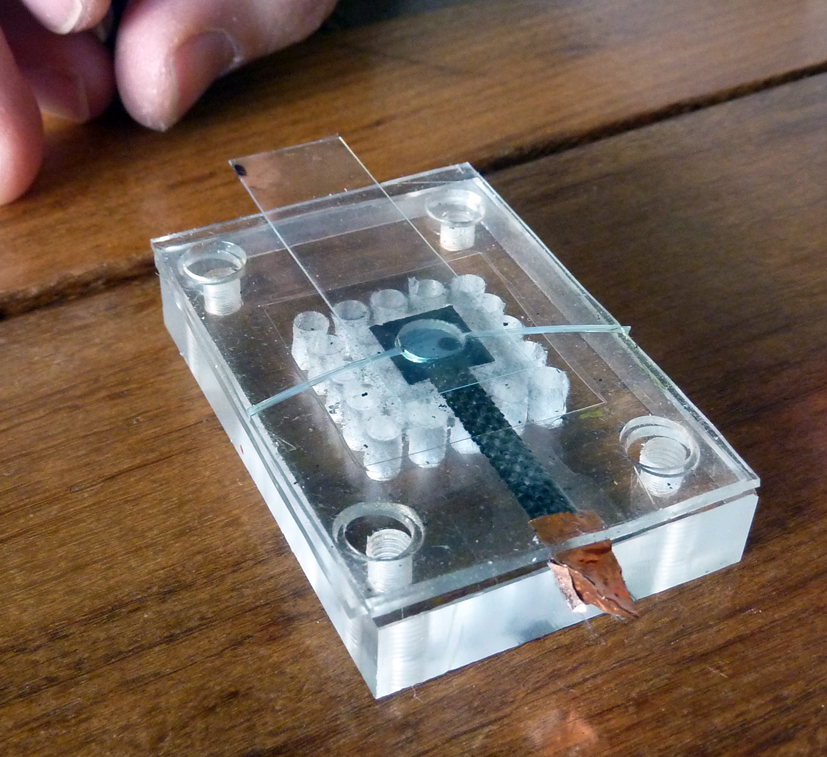

Initially, the design team created visualisations of the scientist’s device using graphic diagrams and 3D computer models. These visualisations served a double purpose: on the one hand, to verify with the scientist if their understanding of the technology was accurate, and on the other, to generate visual material for the exhibition poster.

The design team suggested creating visual representations of potential future uses of the technology to incorporate into the poster. They believed that presenting the technology in this manner would enhance public receptivity and comprehension. Collaborative brainstorming sessions involving engineers, designers, and scientists generated ideas for these future applications.These visualisations formed the foundation of the poster, which was showcased at a science fair in London. The poster received overwhelmingly positive feedback from attendees and proved instrumental in explaining the technology during the event.

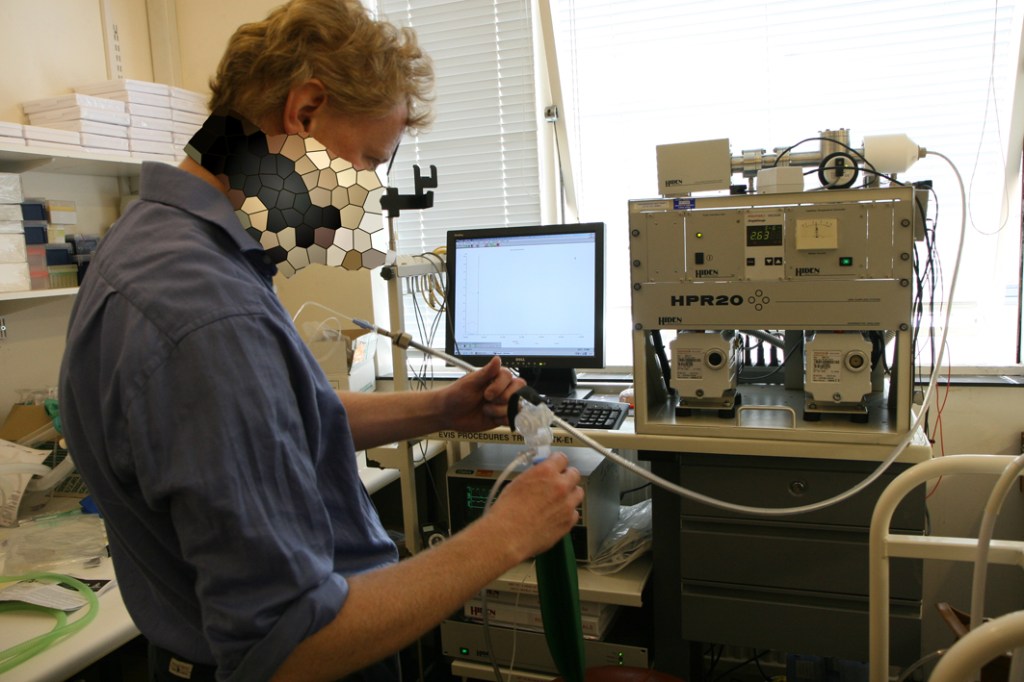

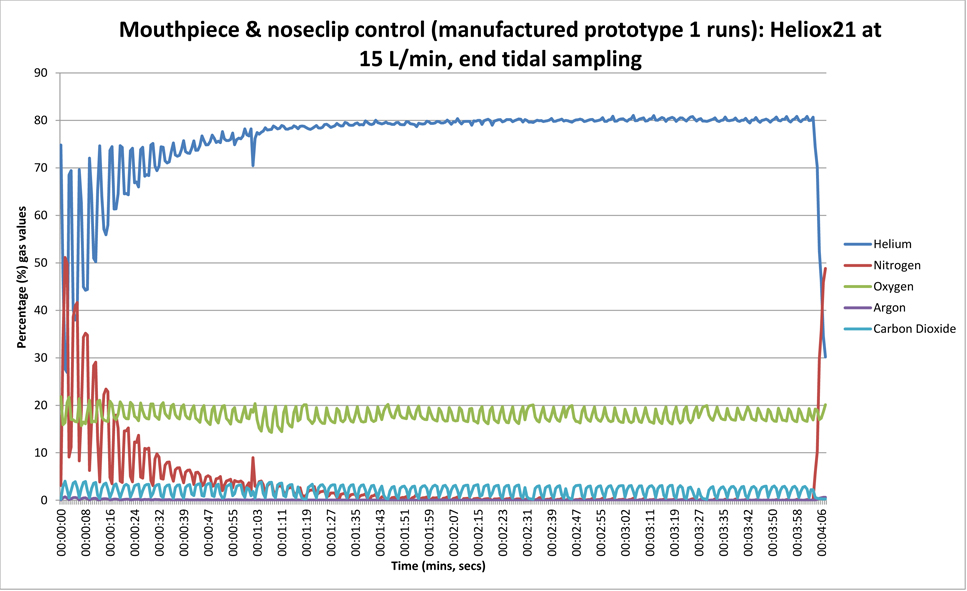

The designers visited the scientist’s laboratory to observe his latest devices, which inspired them to develop a functioning prototype of the “algae solar panel” concept from their brainstorming session. Although it did not generate as much energy as anticipated upon completion and testing, it unexpectedly facilitated the measurement of water produced during the biophotovoltaic process, leading to empirical confirmation of water production and proof of the technology’s potential for desalinating seawater. This demonstrated the value of collaboration between designers and scientists, sometimes resulting in unforeseen and beneficial outcomes.

Encouraged by the positive response to the poster and algae solar panel, the design team saw potential in developing the Moss Table concept—a household item integrating a table and lamp powered by biophotovoltaic energy. They aimed for familiarity by incorporating everyday objects and designed the table to be simple and unobtrusive, complementing the BPV technology.

The table prototype premiered at the Design Festival in London, where it garnered significant interest from the design press, notably from those involved in sustainability initiatives. Although the formal project concluded after its exhibition at the London Design Festival, the team continued collaborating. They showcased the table in Milan, Paris, and Rotterdam, underscoring the project’s achievements. The Moss Table effectively communicated biophotovoltaic technology to a wider audience and drew attention from both the design and scientific communities as well as potential investors.

P3-Oxigen Therapy Mask

2017 / Digital/Visual/Service

Project Partners: Adenbrooks Hospital and Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge.

My role:

Co-researcher and co-designer (Including research, visualisation, ideation, prototyping and testing)

Design Goals

In his respiratory gas delivery research, an anesthesiologist identified the need for a better sealing mask for patient tests. Dissatisfied with existing options, he designed a new mask, achieving nearly perfect sealing in trials.

He recognised its commercial potential and aimed to develop the mask for medical markets. However, his prototype lacked suitability for clinical settings and patient comfort, hindering research and trials. The project aimed to develop a testable mask, seek materials for comfort, and conduct clinical trials to improve oxygen therapy techniques and gas measurement accuracy. The mask should also be designed to suit plans for mass production.

The design team visited the hospital to observe patients with various respiratory issues. They believed witnessing patients in their environment first-hand was essential to better understanding their needs. Following the observation, they evaluated different commercial masks and compared them to the scientist’s concept. Concurrently, they presented a preliminary brief outlining a work plan, product specifications, user demographics, and usage context.

Brainstorming sessions helped explore alternative sealing concepts for masks, seeking to complement the effectiveness of the scientist’s sealing concept. Despite generating several interesting alternatives, the scientists’ concepts seemed similar. Consequently, the team opted to adhere to the main principles of the original idea while experimenting with new materials.

After a series of iterative design iterations involving exploring materials, creating sketches, and developing models, the designers put forth a final design proposal using CAD-generated images. Upon presenting the concept, the team transitioned to the prototyping phase to validate the effectiveness of the design proposal.

A mask prototype was built and presented to the scientist, highlighting its key features, advantages, design criteria, and manufacturing process. The scientist tested the prototype on himself and confirmed its effectiveness in comfort, manufacturability, appearance, and, most importantly, sealing. However, it was agreed that testing the mask on individuals with diverse facial features was crucial.

Following the initial prototype, multiple sealing principles were devised and tested in individuals with diverse facial features, contributing valuable insights for advancing respiratory mask technology. This process facilitated a deeper comprehension of the scientist’s original concept. Additionally, by clearly defining the mask design requirements, the design team established the parameters for future mask iterations, both for commercial production and experimental purposes.

P3-Lab Share E-Platform

2017 / Digital/Visual/Service

Project Partners: MRC Stem Cell Institute and Institute for Manufacturing, University of Cambridge.

My role:

Project conception, co-researcher and co-designer (Including research, visualisation, ideation, web prototyping and testing)

Design Goals

In his respiratory gas delivery research, an anesthesiologist identified the need for a better sealing mask for patient tests. Dissatisfied with existing options, he designed a new mask, achieving nearly perfect sealing in trials.

He recognised its commercial potential and aimed to develop the mask for medical markets. However, his prototype lacked suitability for clinical settings and patient comfort, hindering research and trials. The project aimed to develop a testable mask, seek materials for comfort, and conduct clinical trials to improve oxygen therapy techniques and gas measurement accuracy. The mask should also be designed to suit plans for mass production.

A series of preliminary observations and shadowing activities were conducted in the laboratory. The design team closely monitored the scientists’ day-to-day activities, became familiar with the protocols for research and experimentation, and participated in meetings with the laboratory staff. Based on these observations, the team recognised the need for a platform to enhance communication and facilitate sharing of laboratory protocols among researchers, technicians, and other scientists.

The designers noted a series of tagging actions leading to discomfort and errors. These issues were further compounded by informal methods of information dissemination related to laboratory protocols and equipment usage, such as sticky notes and handwritten papers attached to walls and apparatus. This highlighted the necessity for designing a reliable and formal information-sharing system.

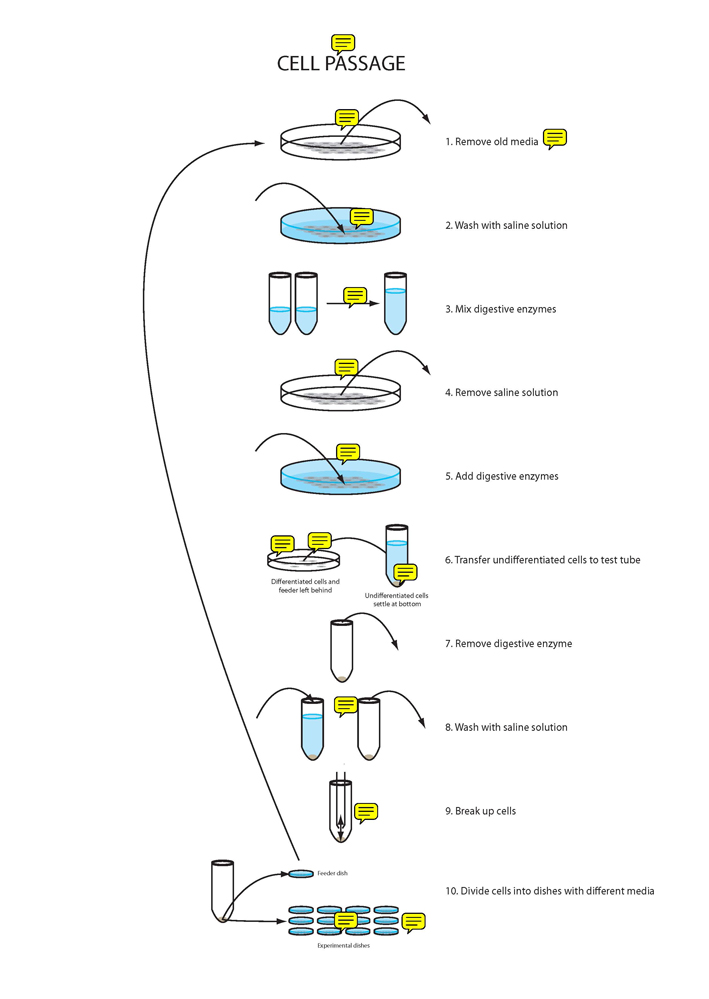

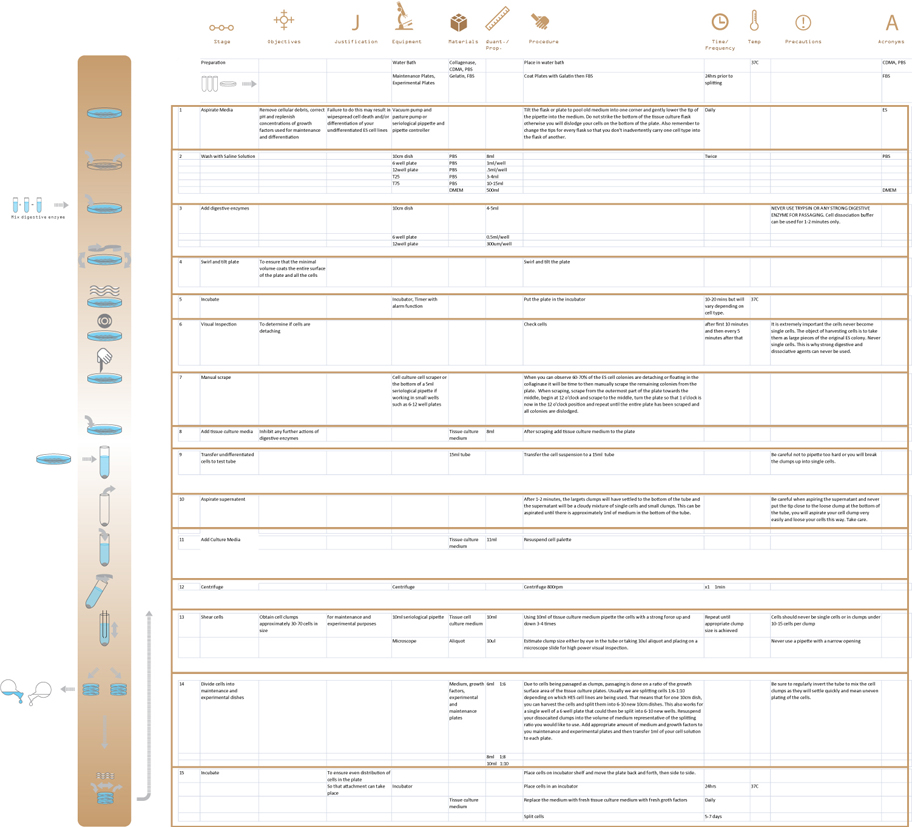

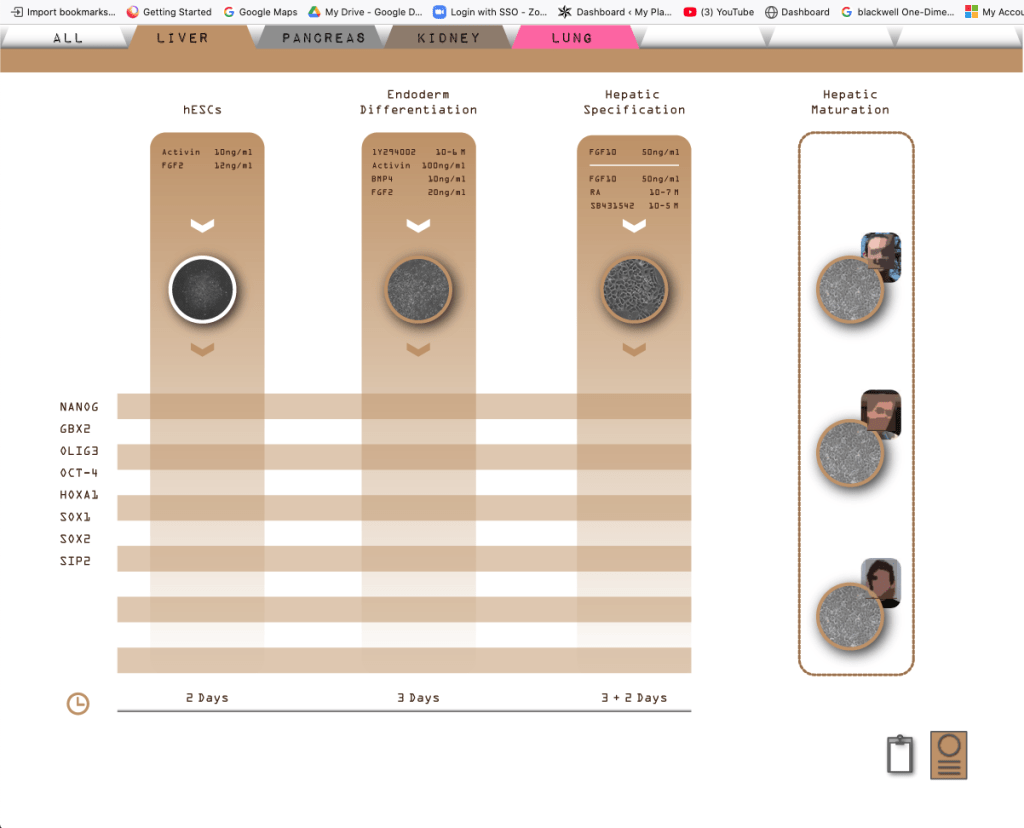

The design team developed a series of visual representations of stem cell research laboratory protocols, first to test their comprehension of these protocols and second to establish a visual language that would effectively communicate these protocols in a manner that was both understandable and well-received by the laboratory staff.

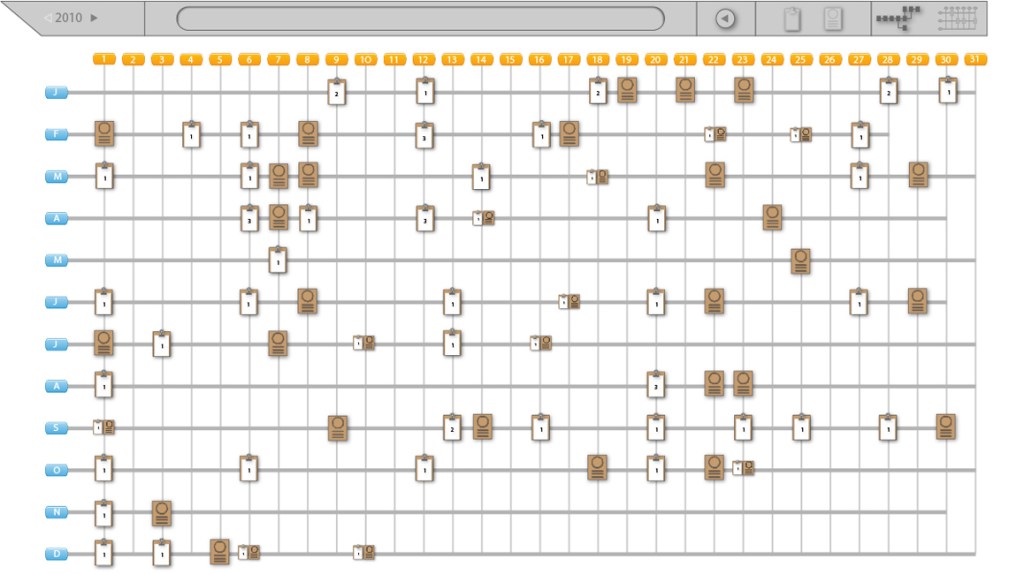

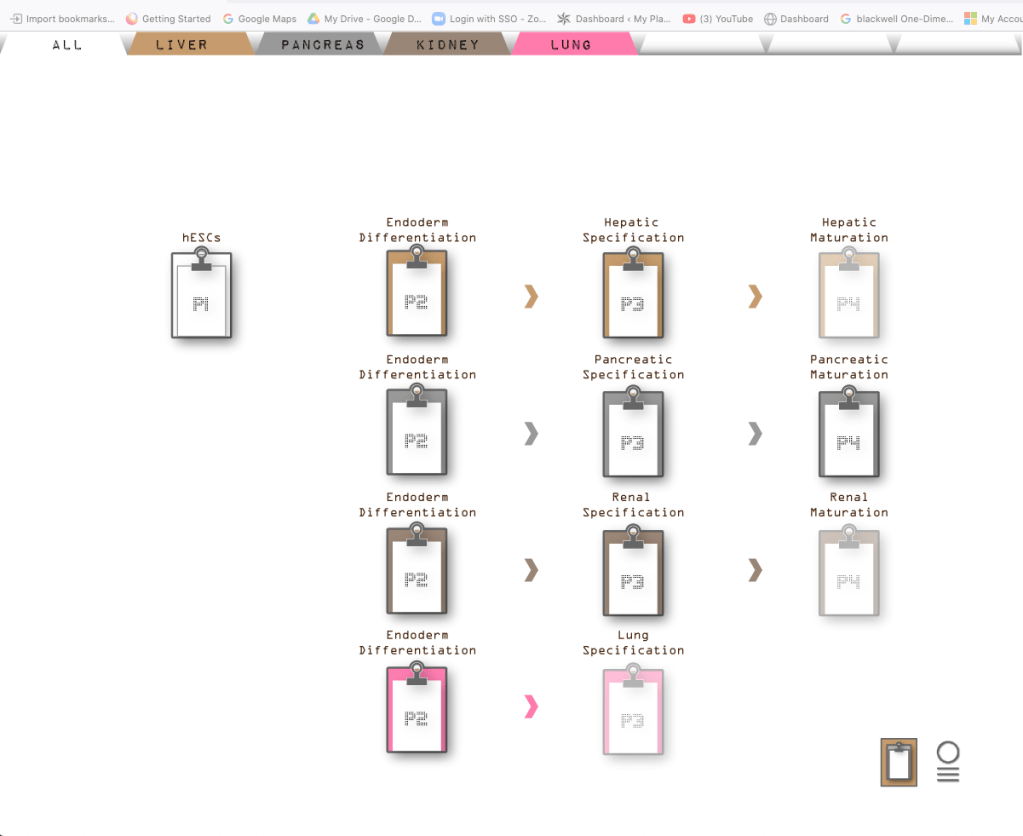

The design team developed an interactive visual system anchored by a diagram illustrating the various stages of stem cell differentiation. This diagram was the foundation for accessing protocol templates and displaying associated “protocol matrices” within a protocol assets library. The designers crafted the user architecture of their interactive system through wireframes, and the tool was realised as a web page. This allowed scientists to access it offline and online, recording, editing, and sharing experiments with colleagues.

A mapping system was incorporated so staff could trace the evolution of protocols’ evolution sequentially, link them to the scientists who developed them, and access specific protocols associated with organ research.

The collaborative development of this e-platform was instrumental in making tacit knowledge about the Cell Passaging protocol explicit and in exploring ways to systematise the communication of stem cell scientific protocols. Furthermore, this collaboration allowed scientists to reflect on their internal communication practices and consider ways to enhance them.